The Politicians Who Oppose Investment Freedom

They would impose their views on others.

Competitive Returns

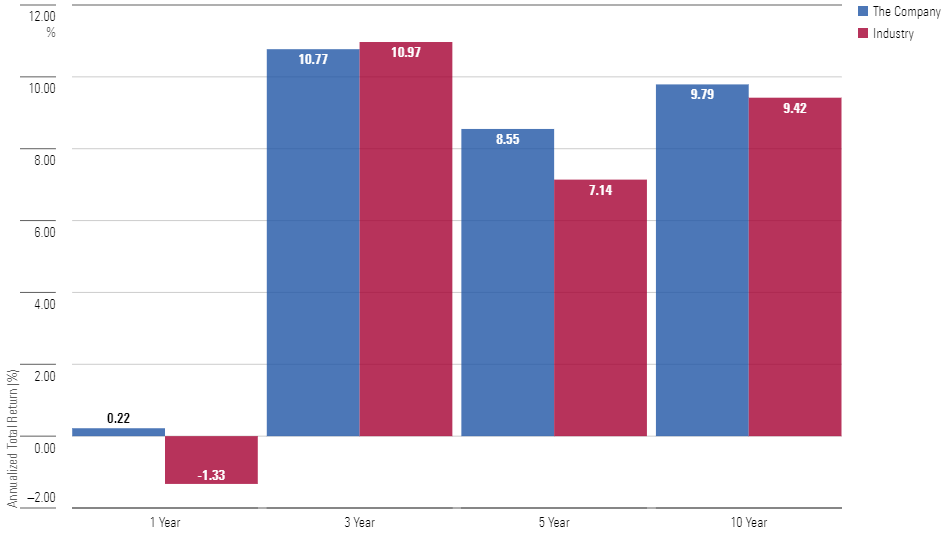

Imagine a large fund family, containing 407 funds (a great many, but Fidelity has even more). Over the trailing five years, the average return for that company’s U.S. equity funds, which control most of the organization’s assets, has exceeded that from three of the five largest providers: Vanguard, BlackRock BLK, and American Funds.

Not bad, right? What’s more, the numbers look similar when the company is compared against the entire fund industry. Its funds slightly lag the three-year average but are ahead over the five- and 10-year periods, as well as over the most recent year. (This and all other computations include both traditional mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.)

All U.S. Equity Funds

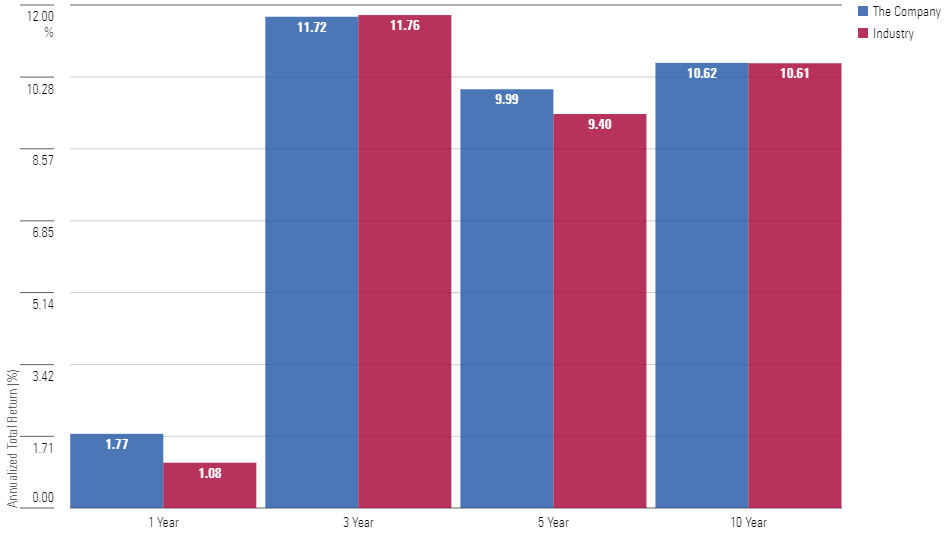

Perhaps that presentation exaggerates the organization’s accomplishments. If its funds have performed poorly relative to others in the same category but have benefited by occupying the most profitable categories, they could look good despite themselves. We can test that possibility by evaluating the flagship Morningstar Category of large-blend funds.

Large-Blend Funds

The apples-to-apples pattern is virtually identical.

Congress Objects

Yes, despite these thoroughly unobjectionable results, the company faces what no other fund organization has ever encountered: Congressional opposition. This month, House Financial Services Committee member Andy Barr (R-KY) reintroduced the Ensuring Sound Guidance Act, which would effectively prevent the company’s funds from being used within 401(k) accounts. They have been deemed uniquely unsuitable. Every fund competitor may proceed as usual, but not this organization.

My hypothetical “fund company,” as you may have already guessed by the proposal’s abbreviation, consists of the industry’s environmental, social, and governance focused funds. Their results are depicted above, and their retirement-plan futures are now threatened.

Without Precedent

Let’s consider how this bill might be defended. The most logical reason for opposing ESG investing is weak investment results. If ESG funds—or, to call them by their newly preferred label, “sustainable funds”—have harmed their investors, then perhaps Congress could justifiably amend Erisa statutes to discourage their inclusion in employer-sponsored retirement plans. However, as we have seen, that has not occurred. No reasonable claim can be made that ESG funds have performed badly.

Also, that explanation wants precedence. There are plenty of demonstrably bad investments that are permitted within 401(k) plans. For example, when I last studied tactical asset allocation funds, I found they had trailed strategic allocation funds (which invest similarly, but without attempting to time the financial markets) by almost 3 percentage points per year. Congress cared not. Nor, to my knowledge, has it ever before addressed any other specific investment strategy.

Free-market supporters will understand why Congressional assistance has not been required. Few 401(k) plans contain tactical allocation funds, because the marketplace has voted with its feet. The same principle has applied to market-neutral and convertible-bond funds: Those investments have not attracted 401(k) plans, because they have not delivered competitive returns. Should they ever do so, 401(k) plans may adopt them—but not before that date.

The Theoretical Objection

Lacking evidence, the attack on ESG investing relies instead on theory. Because ESG investors “put environmental and social goals ahead of returns,” states Rep. Barr, their funds will necessarily trail competing funds that solely evaluate “pecuniary factors”—that is, strictly financial issues. The best way to profit, after all, is to seek businesses that are profitable.

While that contention seems sensible, fund investors have learned the hard way that investing principles are not necessarily straightforward. After all, active fund managers examine profitability while index funds lead completely unexamined lives, yet the latter now dominate the marketplace. Besides, ESG proponents offer a countervailing theory. Over time, they claim, their strategy will beat conventional investing because screening for ESG factors reduces risk. The goal of investment management, after all, is to anticipate future events.

I have no idea which of those two theories is correct, and neither does Rep. Barr, nor ESG supporters. This topic resembles the debate about whether value-style stocks will once again outgain growth stocks, as they have done through much of the past century, or will lag, as has been the case over the past 20 years. Compelling arguments can be made for either side, but nobody knows. (Except, naturally, product marketers.)

It’s Personal, Not Business

If the performance of ESG funds has been acceptable, which it unquestionably has been, and the underlying rationale for the practice cannot be dismissed, then the only reason left to oppose ESG funds is animus. Rep. Barr wishes to impede ESG investing because he dislikes its goals.

Antipathy makes for poor public policy because retribution works both ways. Currently, faith-based funds may be offered within 401(k) plans, without impediment. Those who support Rep. Barr’s bill would do well to realize that it may just as easily be applied to those funds because, as with ESG investing, faith-based funds also evaluate nonpecuniary factors. Following the same logic, should Erisa legislation be used to stymie the investment plans of religious organizations?

Of course not. Attempting that would be shameful. But if Rep. Barr’s bill were to pass, such a possibility would exist.

Today is the 4th of July. The day to honor freedom. Every day should be observed in its spirit.

Isn’t It Ironic?

The Ensuring Sound Guidance Act contains a provision requiring (should customers overcome the various regulatory hurdles the bill would erect against “nonpecuniary” investing), by holding such fund, that their investment advisors be mandated to show them after a period “not to exceed three years” the opportunity cost that they paid by indulging their preferences. The required context is a “reasonably comparable index.”

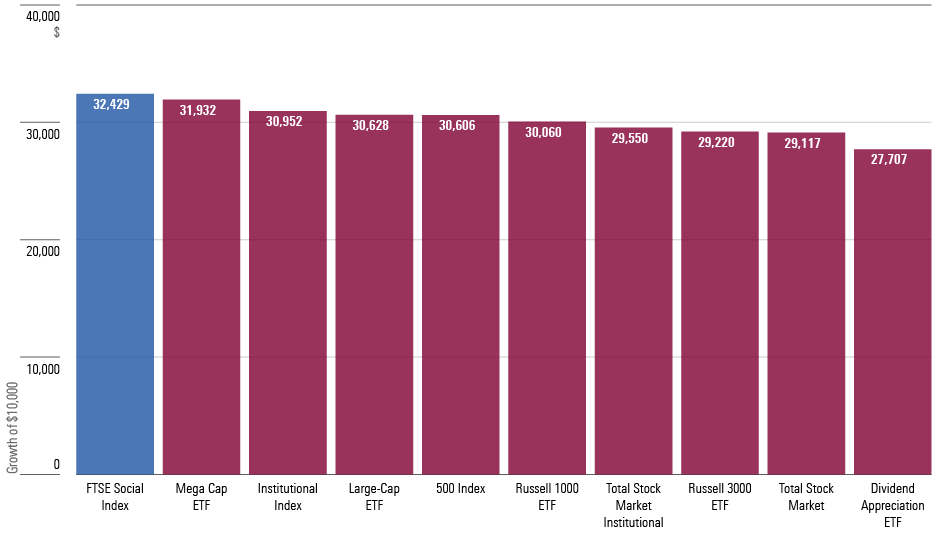

So, I did just that—although I extended the period to 10 years, because only politicians would make investment judgments based on 36-month periods. Below is the trailing growth of $10,000 for all Vanguard large-blend index funds (oldest share class). The lone ESG fund is shown in blue.

Vanguard's Large-Blend Index Funds

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.